Filipino Time

Tracking seasons through the environment, on the meaning of panahon, and a calendar for 2025

Time is a strange thing. The sun and moon, those two celestial beings, “create” time in the most tangible ways through their rotations and consequent effects on our diurnal rhythms, climate, and seasons. The solar year is precisely 365.24 days, the amount of time it takes for Gaia to make a complete orbit around mighty Sol. Little Luna mimics this waltz around us in turn, completing a synodic lunar month in 29.53 days, so that a lunar year contains 354.57 days. This renders it difficult to reconcile both types of years, especially as different cultures throughout history often utilized one or the other.

That these cycles did not fit neatly into one another was well known: back in the fifth century B.C., the Greek poet Aristophanes, in his play The Clouds, had the moon complaining that the days refused to keep pace with her phases.

-Dan Falk in In Search of Time: The History, Physics, and Philosophy of Time

Geologic time operates on an order completely separate from the sun and moon, focused entirely inwards in eternal flux, making its presence known through the drift of tectonic plates and the occasional volcanic outburst. Forget lifetimes, or even generations, the existence of entire species is fractions of a second to a rock.

Another rush of vertigo ensues when we think of astronomical time, the birth and death of stars, galaxies, and the universe itself. At this scale, we begin to see that time is not a thing separate from space, they are one and the same in a continuum. When we look up at the stars, we gaze deep into the past.

Today, time mostly exists within our calendars, endless cycles of Mondays to Sundays, Januaries to Decembers. The Gregorian calendar is one of the most wildly successful ideas in human history, and its uniformity and ubiquity make sense in today’s global economy. However, before the Spanish brought over Old Gregory’s system, Filipinos employed a wide variety of methods to keep track of time. In fact, we did not even have a word for time, we traced its passage through the ‘cultivation of the soil, counted by the moons, and the different effects produced upon the trees when yielding flowers, fruits, and leaves.’

Tracking Seasons

In the Cordillera Range, the advent of a specific bird is the key signifier of the “New Year”; the beginning of the sowing season.

That bird called kiling or kiwing… for if they sow their seedbeds when he makes his distinctive cry, their rice will flourish when the mountain streams are swollen and be ready for harvest before the water courses dry up again. To be more specific, one should start to sow not when the baby kiling can only chirp "ki-ik" for when he has developed his full-throated "kiling!”

As life in the Cordillera is centered entirely around the agricultural season, it is only natural that their timekeeping does as well, remaining as variable as the annual fluctuations of the local climate. Anticipating the incoming rainy season is critical to maximizing crop production; in lieu of advanced meteorological systems, tracking the patterns of migratory birds suffices as an accurate indicator of seasonal shifts. The Philippines sits squarely in the middle of the East Asian-Australasian Flyway, serving as a rest stop for birds that migrate North to South and back again throughout the year. Our avian guests such as the Siberian Rubythroat are far more sensitive to temperature and precipitation patterns than us bipeds, choosing the right time to mate and prepare their nests.

The phenological patterns of plants also serve as an important indicator. In the Cordillera, the fiery blooms of the Geb-geb tree typically align with the arrival of the Siberian Rubythroat. The Tiruray in Mindanao used the flowering of the wild forest tree Keguku (Syzygium calubcob) to indicate the beginning of the marking season for their swidden practices. In the Ilocos region, months were named after the trees that flowered then, such as Sagat (Vitex parviflora) and Banaba (Lagerstroemia speciosa).

The Igorot actually developed and utilized a solar calendar, yet they employed the services of a village timekeeper to account for leap years by consulting his plants. The timekeeper “calculated by the position of the stars and by the angle of the sun's rays observed in a certain small ravine where are grown certain plants known to flower, fruit and change their leaves on about the same day each year.”

Volcanic Legacies

While geologic time operates on a scale incongruous with daily human life, volcanic eruptions are important time-bound markers in indigenous Filipino histories. Mount Mayon in Bicol is a prominent, active volcano that has conferred a local identity on its nearby inhabitants. Its volcanic soils are rich in nutrients and perfect for growing crops, but there is always the inherent risk of encroaching too near, given the frequency of its eruptions. Several eruptions in the latter half of the 19th century, for example, forced the relocation of over 8 nearby towns. This may have been a regular occurrence dating back hundreds of years, as indicated in the regional folk epic Ibalong.

While some Bicolano communities are named after local flora, others reference the volcanic movements of Mayon directly, such as the town Binanwaan, translating to ‘that which was abandoned and has been restored’, or Magapo, ‘rock-strewn area’.

Mount Pinatubo further to the north, while not as active, has left long-lasting cultural imprints in local legends. Before the calamitous eruption of 1991, the previous suspected eruption of Pinatubo is estimated to have occurred over 500 years ago. Still, indigenous Aeta legends contain clear elements of volcanism.

Bacobaco climbed Mount Pinatubu in exactly twenty-one tremendous leaps. When he had reached the top, he at once began to dig a big hole into the mountain. Pieces of rock, mud, dust, and other things began to fall in showers around the mountain. All the while, he howled and howled so loudly that the earth shook. The fire that escaped from his mouth became so thick and so hot that the pursuing party had to turn away. At the end of three days he stopped, and all was quiet again in the mountain. But the lake with its clear water was now filled with rocks, and mud covered everything. On the summit of Pinatubu was the great hole, through which Bacobaco had passed, and from which smoke could be seen constantly coming out. This showed that although he was already quiet he was still full of anger, since fire continued to come from his mouth…

This excerpt collected in 1915, survives only as a garbled typewritten transcription on microfilm in the Filipiniana collection of the University of the Philippines. It carries special weight because it was collected long before geologists recognized that Pinatubo was even a volcano (Rodolfo & Umbal, 2008).

Indigenous Starlore

As with many cultures around the world, the astronomical patterns of stars and constellations served as important time-bound markers. In the Cordillera, the Igorot “govern themselves by one star that rises in the west, which they call Gaganayan, [Ganay in modern Igorot is the fertility of plants; gaganayan ought to be "most fertile" or "place of great fertility."] On seeing that star they attend to the planting of yams and camotes, which form their usual and natural food" (Blair and Robinson, 1909). Gaganayan is very likely the star Sirius, the ‘dog star’ named by the Romans whose rising indicated the beginning of the ‘dog days of summer’. To the Igorot, perhaps the ‘camote days of summer’ would be more appropriate.

The Tiruray similarly tracked several constellations, such as Kufukufu (Pleiades), a swarm of flies in the heavens buzzing around the rotting jawbone Baka (Hyades) of a wild pig, slain by a celestial hunter Seretar (Orion). Where the Tiruray saw in the Pleiades a swarm of flies, the Yakans of Basilan saw a school of fish, indicating the opportune moment to set forth their bubo or fish traps.

Panahon

Eventually, the word Panahon came to be widely used to mean Time among Bisayans and Tagalogs, however not in the same way that the Spanish used it. It was used to signify seasons and climates, or as indicated in a Tagalog dictionary from 1620, the “time in which one initiates or harvests something.” This is reflective of the way Filipinos mark time, not in the absolute, but much in the same way indigenous cultures used plants, birds, volcanoes, or the stars- to mark the intervals of societal rhythms and human life.

The root of panahon takes this a step further, derived from the Malay “tahun” meaning opportunity. Heidegger stumbled upon this centuries later in his Dasein, his “being-in-the-world”. He rejected the Cartesian notion of the human as a spectator, presenting instead the inseparability of human existence with the world that surrounds us. What Heidegger called Augenblick, he might have instead simply used Panahon, a concept of time that escapes Western metaphysics of absolute everydayness, and situates us instead in a position of opportunity and possibility.

A PlantVision Calendar

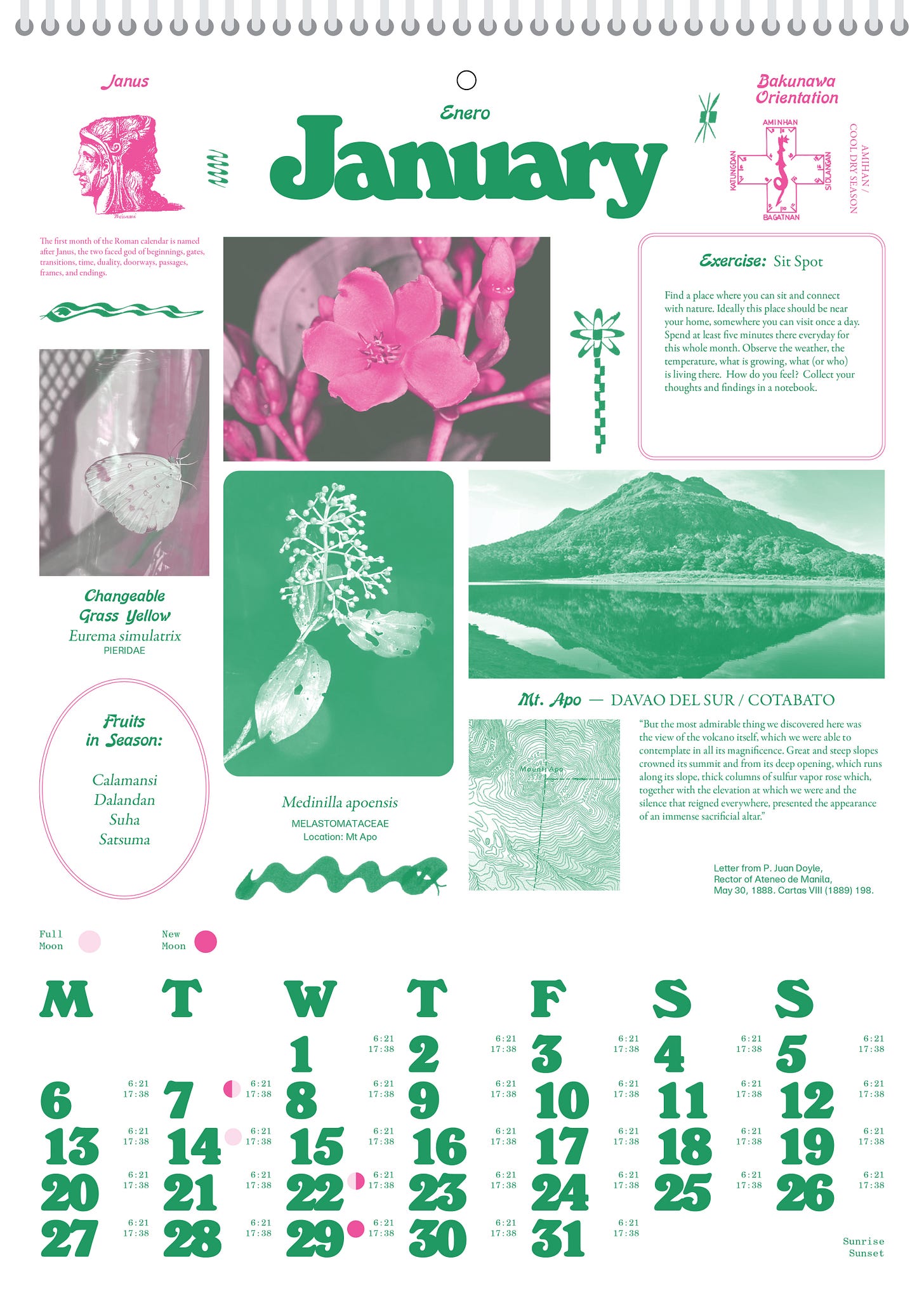

As the year (in the Gregorian sense) comes to a close, we wanted to create a calendar that embodied panahon. Each page in the calendar contains information on mountains, some species that occur there, the orientation of the mythical bakunawa, the shifts between habagat and amihan, the appearance of indigenous stars such as Gaganayan or Kufukufu, and more.

We want this calendar to be a reminder not just of your upcoming tasks and events, but of our ecological entwinings, that time is more than the march of entropy and is rather a uniquely human experience.

Written by John Altomonte.

Before you go, do consider purchasing a calendar for you or your loved ones who love plants. All proceeds are donated for research and conservation of Philippine forests. Thanks, we love you!

My wife also insists that you complement this read by listening to Kanlungan by Filipino folk-singer Noel Cabangon, who sings “Pana-panahon ang pagkakataon, maibabalik ba ang kahapon.”

References:

Rodolfo, K., Umbal, J. (2008). A prehistoric lahar-dammed lake and eruption of Mount Pinatubo described in a Philippine aborigine legend. Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research, 176(3): 432-437.

Bankoff, G., Newhall, C., Schrikker, A.F. (2021). The charmed circle: mobility, identity and memory around Mount Mayon (Philippines) and Gunung Awu (Indonesia) volcanoes. Human Ecology, 49(2), 147-158.

Badillo, V. (1980). Time Keeping: Philippine Style. Philippine Studies, 28(3), 354-362.

Scott, W.H. (1958). Some Calendars of Northern Luzon. American Anthropologist, 60(3), 563-570.

Schlegel, S. (1988). The Traditional Tiruray Zodiac - The Celestial Calendar of a Philippine Swidden and Foraging People. Philippine Quarterly of Culture and Society, 15(1/2), 12-26.

We would also like to thank Pecier Decierdo for his insight and expertise in tracking stars and their indigenous lore, and Wild Birds of the Cordilleras for identifying local avian fauna.