Let it Rot

The problem with permanence and learning to embrace decomposition

In a recent chat with a friend over coffee, we ran through the typical lighthearted conversation topics: geopolitics, the climate crisis, environmental collapse, you know, the works. In the middle of all this banter and gaiety, a particular comment she made stood out to me. She said that it seemed as if the world is currently in a state of decomposition, both societally and physically.

This imagery, that of rot and decay as something bad, is all too common in today’s parlance. Perhaps only a gardener will take the opposite view. These green-fingered fellows know the feeling all too well; a handful of deep, rich brown, almost black, soft, crumbling between our fingers. The direct outcome of decomposition, compost, is nigh panaceic in one’s garden. The initial stench of rot gives way over time to that earthy smell we so adore in good compost and healthy soil. That scent has its origins in the machinations of actinomycetes, a semicolonial bacterium.

The actinomycetes are just some of the denizens that reside below our feet- for all the immense diversity aboveground, at least an equal amount lives within the soil. Decomposers of all kinds, springtails, worms, nematodes, bacteria, and fungi, take all sorts of matter and repurpose it into usable nutrients that are then taken up through root systems. These root systems are just as active, stabilizing soils and breaking apart harder minerals. Life belowground congregates around these roots, just as active a niche as anything above the surface. A small handful of soil reveals a Lilliputian world unto itself, teeming with these alchemists of rot. Henry Miller put it best, that “it is almost banal to say so, yet it needs to be stressed continually: all is creation, all is change, all is flux, all is metamorphosis.”

Despite having meant something else entirely, my friend was right. The world absolutely is in a state of decomposition. It always has been so. Every form of life, every being aboveground, is destined for the soil.

Death and life are two sides of the same coin; they are both the earth reweaving itself into something new, a constant reincarnation, a facet of eternity.

Death is beautiful when seen to be a law, and not an accident — It is as common as life… Every blade in the field — every leaf in the forest — lays down its life in its season as beautifully as it was taken up. When we look over the fields we are not saddened because these particular flowers or grasses will wither — for their death is the law of new life.

- Henry David Thoreau

Perhaps the issue is not with death, decay, or decomposition but our resistance to it. Humanity’s obsession with permanence has led to a refusal to succumb to rot; greenhouse gases lodged in our atmosphere that drive the climate crisis, and plastics that litter every stratum of the biosphere, now embedded in our very cells. These byproducts of “growth” defy the eon-spanning dance of life and death, ironically sending us towards total system collapse.

Instead of resisting rot, perhaps we should learn to revere it. Let that misguided myth of economic growth decompose! Trust in the quiet labor of worms, the mysteries of fungi, and the wisdom of actinomycetes; trust in the fact that all that you are, flesh and bone, was once fern, feather, ash, stardust. Trust that it will happen again. Death was not an end for all that came before, but a return. In embracing rot, we might yet become fertile ground for something more beautiful, more alive.

Written by John Altomonte

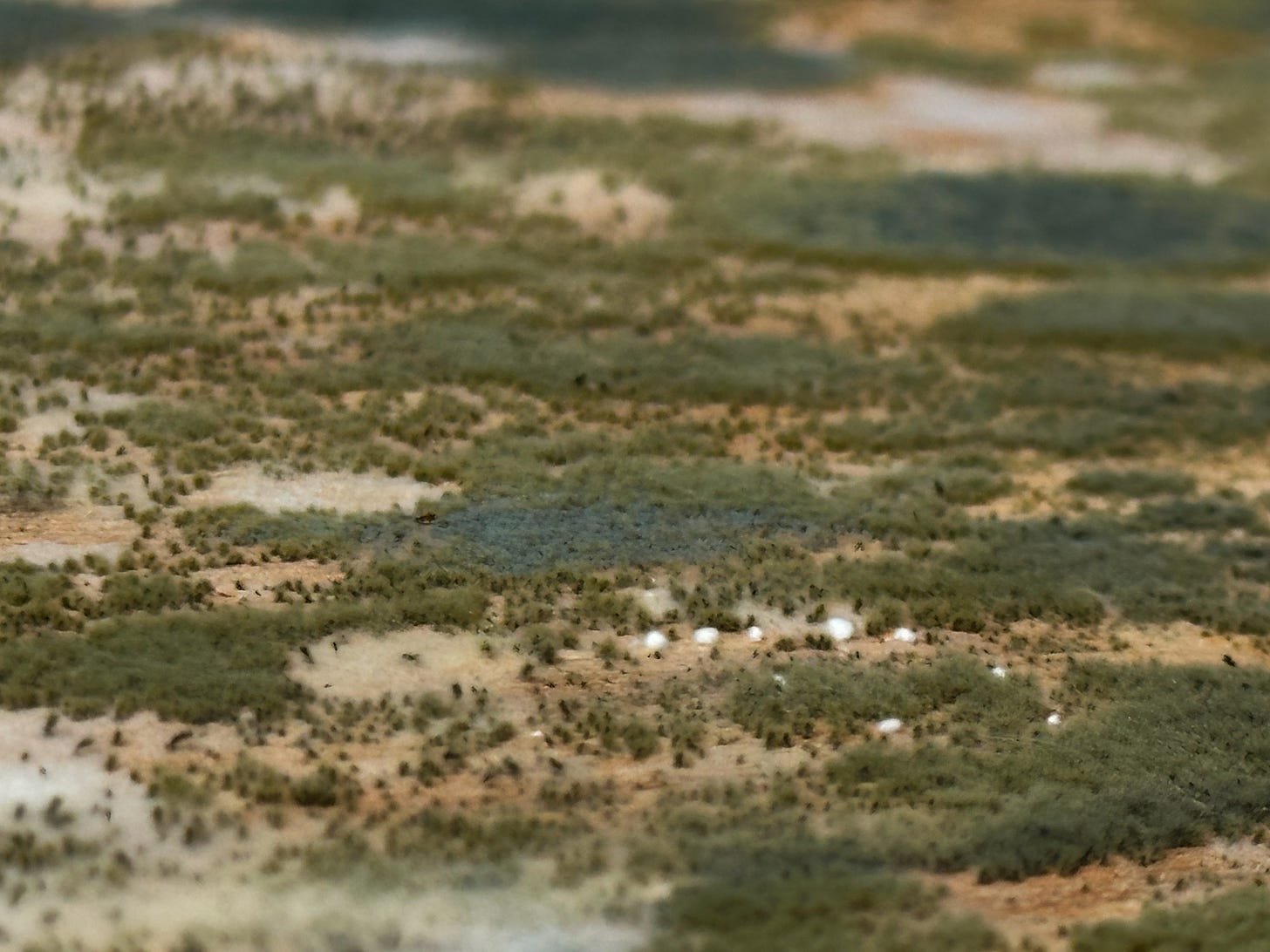

Moldscapes by Monica Ramos

That was nice. The only thing I can suggest is that you also take care to quote a few of the many inspirational women who have understood metamorphosis. The world has produced so many, from different eras and societies. After all, we all realize that women were the "gatherers" in the "hunters and gatherers" version of earlier human groups, so they had to have understood plant life, growth, death and decomposition intimately - or we would not be alive today, since gatherers supplied most of the food. For a Northern European example of a revered woman who knew, try Hildegard of Bingen.