I have hazy, fragmented memories, half-crystallized in my hippocampus, from my childhood. In the high-walled subdivision where I lived, there was an empty lot of land right by my house: the only nearby patch of ‘wilderness’ I had access to. Desolate to most adults’ unseeing eyes, it was a simple two-hundred square meter patch of cogon grass (Imperata cylindrica), the only potential it held was that of a future development; steel, concrete, and millions of pesos transferring hands.

To me its potential was vast and limitless, a New World, mine to discover. My first discovery, and perhaps still one of my favorite plants today decades later, was that of the mahakiya (Mimosa pudica), a creeping member of the legume family (Fabaceae). Amidst the swathes of grass, you would be able to find small clumps of makahiya, its bright pink flowers a dead giveaway. Its name, makahiya, means “shy” or “embarrassed” in Tagalog because of its propensity to physically retreat from the slightest sensation, a gentle touch, a gust of air, or a small child’s rustling about. Its leaves are bipinnately compound, little pairs of leaflets perching on opposite ends of the main leaf stalk, called a rachis. These leaflets, when overstimulated, fold upwards, closing off the leaf from the world, reacting instantaneously much as an animal would. This evolved trait, termed seismonasty, allows the makahiya to perhaps defend against would-be herbivores or pests, a rapid, mechanical function seldom seen in the plant world. It also served as an important lesson for me- that plants were alive. Perhaps a simple and obvious lesson, but one that is often forgotten.

Somewhere along the temporal path toward gaining full adult consciousness, wonder and curiosity were replaced with the anxiety and stress of modern human life. Income! Taxes! The future! Struggling with these existential threats and without my noticing, the empty lots of Manila, these patches of wilderness, dwindled and disappeared, and my ability to see and recognize plants with them. I had become plant blind.

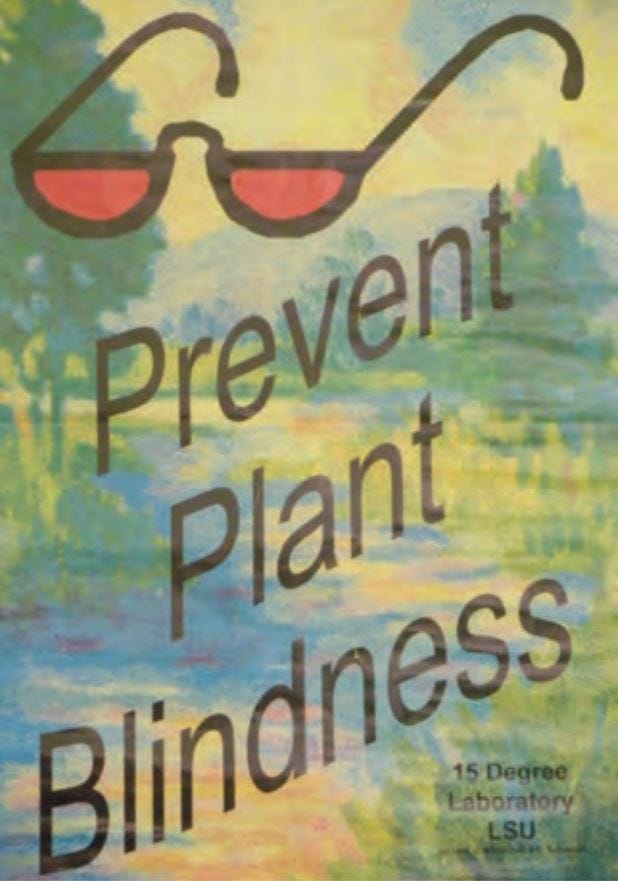

On the cusp of the new millennium, James Wandersee and Elizabeth Schussler introduced the term ‘plant blindness’ after decades of research and “a fair amount of trepidation”. The environmental movements of the previous decades (a topic for another time) had spotlighted the extinction crisis in the animal kingdom. The plights of pandas and polar bears had captured the public imagination, but their plant-based environments faded into a hazy, green background. After conducting surveys on US students and finding only 7% had an interest in plants, Wandersee and Schussler launched a national campaign targeting schools and science conventions with a poster that simply states, “Prevent Plant Blindness”.

In Wandersee and Schussler’s words, ‘the poster is designed to be initially puzzling. It shows a tree-lined, riverine environment emblazoned diagonally with the words "Prevent Plant Blindness." Hovering, Magritte-like, in the sky above is a pair of dark-red-tinted spectacles. The implication is that someone wearing these glasses could not see the green plants in the scene below- that if one's vision is "filtered," either physically or conceptually, one may easily miss seeing the plants that appear in one's field of vision.’

The initial definition of plant blindness, put forth by W&E, went as such:

(a) the inability to see or notice the plants in one's environment;

(b) the inability to recognize the importance of plants in the biosphere and in human affairs;

(c) the inability to appreciate the aesthetic and unique biological features of the life forms that belong to the Plant Kingdom; and

(d) the misguided anthropocentric ranking of plants as inferior to animals and thus, as unworthy of consideration

While not officially on online repositories such as WebMD, W&S outlined some key symptoms of the cultural malady which you can use hypochondriacally to diagnose yourself or those around you.

Do you:

think that plants are merely the backdrop for animal life?

fail to see, notice, or focus attention on plants in one's daily life?

misunderstand what plants need to stay alive?

overlook the importance of plants to one's daily affairs (Balick & Cox 1996)?

fail to distinguish the differing time scales of plant and animal activity?

lack hands-on experiences in growing, observing, and identifying plants in one's own geographic region?

fail to explain the basic plant science underlying nearby plant communities including plant growth, nutrition, reproduction, and relevant ecological considerations?

lack awareness that plants are central to a key biochemical cycle-the carbon cycle?

are insensitive to the aesthetic qualities of plants and their structures-especially with respect to their adaptation, coevolution, color, dispersal, diversity, growth, pattern, reproduction, scent, size, sounds, spacing, strength, symmetry, tactility, taste, and texture (Wandersee & Schussler 1998a)?

If you answered yes to any of these, then you may have plant blindness. Please sign up for the next Plant Vision Field Trip immediately to address this!

Despite the warnings issued from the Magrittesque specter in Wandersee and Schussler’s poster, I was oblivious to the fact that I had been moving through my early adulthood with these red-tinted spectacles firmly perched on my face. Kierkegaard once lamented in Either/Or that “I cannot see the grass grow, but since I cannot I don’t feel at all inclined to.” While less existentially inclined, I had similarly failed to perceive the stillness of the plant kingdom. The slowness of plant life led me to ‘other’ them, an unconscious action that persists across human culture. The tranquility of plants relegates them to a background within which humans and animals move about. And yet, as Dawn Sanders argues, perhaps this othering of plants is a trait that we humans have misguidedly placed on them, and that it is human perception that is stuck in time!

A quick look at the science shows us that this is true. Kingdom Plantae, temporally and spatially, dominate Planet Earth. If we use carbon, that element that defines life (and when covalently bonded with oxygen could destroy it) as a measure of relevance, plants constitute the vast majority (82.5%!!) of global biomass. Humans, in comparison, are a blip, a speck, racing and jostling and hurtling past our elders, our plants, upon whose shade we grew underneath.

Unaware of what I couldn’t see, I stumbled and bumbled my way through life. Despite my work in the environmental sciences, plants still only served as habitats and niches of subjects, but rarely themselves the subject of study. In 2020 however, the human world stopped, and the jolt of it knocked the red spectacles from my face.

Quarantined in the house I grew up in, my restlessness led me to pace the garden my dad tended. Lo and behold, a spot of pink drew my eye to the ground and onto a lone makahiya nestled beside an aloe vera. Just as I did as a kid, I brushed my hand over its leaves and watched the plant retreat into itself, folding up its leaves in consternation at my prying touch. Grinning impishly and delightedly, my vision began to slowly return.

Fast forward four years to the birth of (you guessed it) Plant Vision. At the heart of what we do at Plant Vision is to educate, to make visible, and to carry on the work of the Lorax in speaking for the trees. We do this by creating art and zines, by hosting guided botanical hikes, and by collaborating with institutions such as the Philippine National Herbarium. There is an incredible nexus between disciplines and sectors that we want to explore, all with the ultimate intention of turning plant blindness into plant vision.

This newsletter is one such method, transmitted via electrons and fiber optic cables to LED screens worldwide, where we plan on sharing stories, exploring a myriad of botanical topics, and in general giving recommendations for addressing plant blindness.

Do read, share, then go outside and touch some grass.

Thanks for reading Plant Visions! If you haven’t yet, do also give us a follow on Instagram. We love you.

References

Bar‐On, M. Y., Phillips, R., & Milo, R. (2018). The biomass distribution on Earth. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115(25), 6506–6511. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1711842115

Sanders, D. (2019). Standing in the shadows of plants. Plants, People, Planet, 1:130–138. DOI: 10.1002/ppp3.10059

Wandersee, J. H., & Schussler, E. E. (1999). Preventing plant blindness. The American Biology Teacher, 61(2), 84–86. https://doi. org/10.2307/4450624

Love this! I’m also an advocate for seeing plants

Great to see this given a name! :-) I've always been obsessed with plants but had basically no interest in animals, and have wondered what could explain it. Some of it could be that a big part of the interest is plant distributions, and unlike animals they're tethered to a place. (And the one aspect of animals that I do get into is biogeography, on a large scale.)

One thing that's confounded me in particular (being a palm fanatic) is that so many people seem to think all palms are the same species. They clearly notice them in general (they're essential to creating that tropical feel, after all) but can't make any distinctions. They all must have coconuts, right?