Revelations from the Baylan

A review of the film 'Baradiya' and reflections on pre-colonial histories and decolonial futures

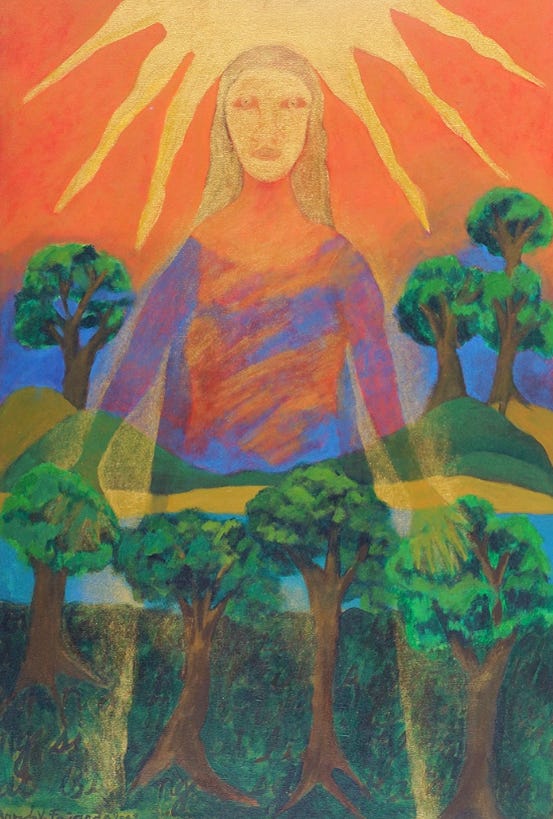

Before the Spanish came with notions of a Catholic God, the Patriarchy, and Environment as Economy, an animist Philippines held a unitary perspective of the universe, allowing them to view the individual, societal, spiritual, and cosmic as part of a single continuum. Indigenous shamans known as the baylan1 helped to navigate the spaces between humans and nonhumans. The short film “Baradiya”, launched as part of The Baylan of Mt. Kalatungan exhibition at the National Museum of Anthropology ‘sheds light on the people and places that form the final vanguard of environmental protection, the indigenous people who call the forests call their home, their sanctuary, their place of worship. Taking off from the experience of the Baylan, who are the only people left to ensure the spiritual continuum of our forests, the project seeks to queer our collective perspective of forests, and to pollinate a dream where our forests are freed from oppressive binaries and structures that hinder its healing.’

Put together by the Kulahi with Emerging Islands, the film follows the non-fictional story of Krystahl Guina, a queer Talaandig-Manobo indigenous youth leader and performer, documenting her struggles with discrimination and her journey of acceptance as a baylan.

The plight of today’s baylan sits in stark contrast to their traditional role in Philippine culture. Animist indigenous peoples had a kinship system that allowed for nuanced gender constructs, where men and women2 could assume various leadership positions. The baylan were spiritual mediums while the sultan and datu filled the political-military roles of the secular leadership3. While the baylan were predominantly female, and the sultan and datu predominantly male, there were vague, nebulous distinctions between these roles. The baylan could assume political leadership, while the datu could preempt spiritual functions. Similarly, it was common for males to adopt feminine roles as baylan.

The baylan’s role as a spiritual medium was inherently ecological, as spirit and environment were not seen as separate things. In their commune with nature, they likely understood what Goethe termed “the individuality, particularity, and metamorphosis of plant form, and the contingent, unsystematic energy of nature in general”.

Animist societies may have viewed nature in a similar, non-binary framework; even adopting a Linnean perspective, the separation of male and female individuals in flowering plants is rather uncommon- most plants are either male and female reproductive parts on the same flower (hermaphroditic) or male and female flowers on the same individual (monoecious). Even for dioecious plants (individuals are either male or female) this is not necessarily fixed and they may go through a process of sequential hermaphroditism such as in the case of the Fortingall Yew, one of the oldest beings in Europe. The 5,000-year-old Yew is male, but in 2015, scientists from the Royal Botanic Garden of Edinburgh noticed that one branch had changed sex, and bore berries for possibly the first time in its storied life.

As the colonization of the Philippines progressed, Spanish missionaries were quick to cry witchcraft and heresy and launched concerted efforts to trample animist beliefs into the ground. An account of a missionary in Zambales in 1605 went as follows:

Fray Rodrigo, on passing through a thicket consecrated to their devils (where, as their rites said, it was sacrilege to cut or touch any branch - besides the great fear that they had conceived that if anyone should have the audacity to do, or to take the least thing, he would surely die immediately), saw a tree covered with a certain fruit which they called pahos, that resemble the excellent plums that we know in Europe.

The good religious, arming himself with prayer and with the sign of the cross, and repeating the antiphony, Ecce crucem Domini: Fugite partes adversae. Vicit leo de tribu Juda, began to break the branches and to climb the tree, where he gathered a great quantity of the fruit. . . . The Indians looked at his face, expecting every moment to see a dead man. . . . Thereupon, all of them, convinced and surprised, not one of them being wanting, followed him axes in hand, and felled that thicket, casting contempt on the devil; and many infidels ended by submitting to the knowledge of the truth.

Over the course of several hundred years, indigenous beliefs were ruptured. European power dynamics between man and woman replaced fluid indigenous norms while nature became something apart from society, its spirits replaced by devils to be destroyed and turned into products for capitalist institutions. The decimation of forests began its long, downward spiral, making way for agriculture or being cleared for timber use. Baradiya highlights this modern disconnect resulting from centuries of forced Western ideology. Krystahl’s non-conforming gender role, which would not have merited a second thought in Philippine animist societies, is now subject to discrimination. Her struggles with self-determination remind me of Robin Wall Kimmerer’s efforts to rally against colonization, particularly linguistic imperialism, or the overwriting of language and names; ‘the replacement of the language of nature as subject with the language of nature as object.’ Kimmerer similarly looks to her indigenous, animist heritage for inspiration and proposes a new pronoun that originates from the Anishinaabe word for ‘beings of the living Earth’: Bemaadiziiaaki.

“Ki” to signify a being of the living Earth. Not “he” or “she,” but “ki.” So that when we speak of Sugar Maple, we say, “Oh that beautiful tree, ki is giving us sap again this spring.” And we’ll need a plural pronoun, too, for those Earth beings. Let’s make that new pronoun “kin.” So we can now refer to birds and trees not as things, but as our earthly relatives. On a crisp October morning we can look up at the geese and say, “Look, kin are flying south for the winter. Come back soon.”

Language can be a tool for cultural transformation. Make no mistake: “Ki” and “kin” are revolutionary pronouns. Words have power to shape our thoughts and our actions. On behalf of the living world, let us learn the grammar of animacy. We can keep “it” to speak of bulldozers and paperclips, but every time we say “ki,” let our words reaffirm our respect and kinship with the more-than-human world. Let us speak of the beings of Earth as the “kin” they are.

We see Krystahl rekindle this kinship in Baradiya, marching through her village which we see sliced in twain and bulldozed into submission, its sediments bared and stark against their green “kin”. She finds her way deep into a forest, where she begins to accept her role as baylan.

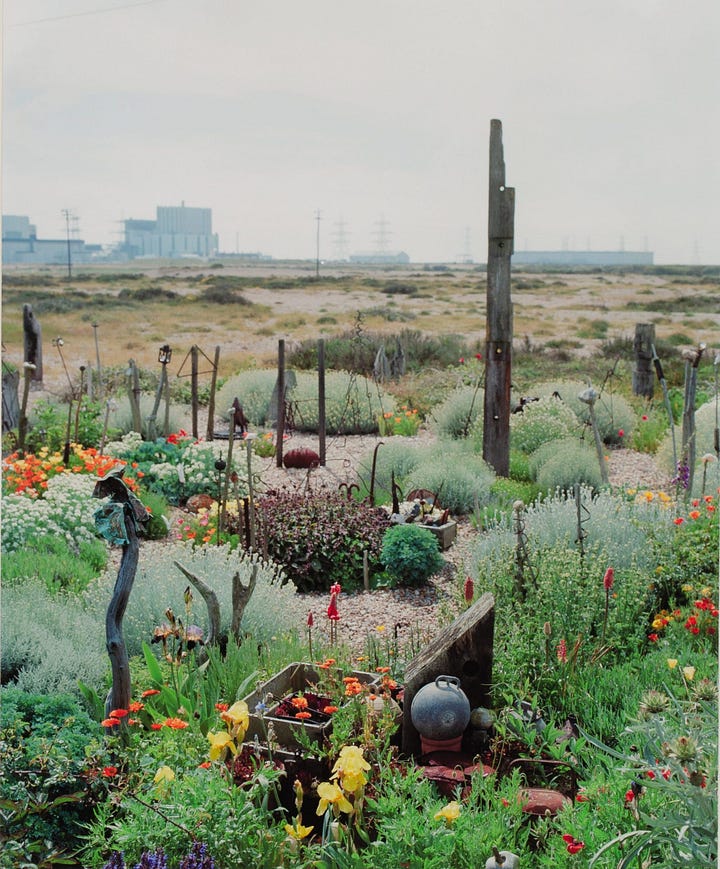

Derek Jarman immortalized a similar flight in his memoir ‘Modern Nature’. After being diagnosed with HIV, Jarman left London for a simple life in the Dungeness countryside, trading the world of filmmaking for gardening. As he gardens, he echoes Blake’s Urizen and its eternal struggle to simultaneously define both itself and the universe. He searches for meaning, slowly accepting the temporality of nature, of all beings, himself included.

As he hears news of a summit on climate change, Jarman pens a letter to a future visitor:

to whom it may concern

in the dead stones of a planet

no longer remembered as earth

may he decipher this opaque hieroglyph

perform an archeology of soul

on these precious fragments

all that remains of our vanished days

here — at the sea’s edge

I have planted a stony garden

dragon tooth dolmen spring up

to defend the porch

steadfast warriors

We can imagine this being addressed directly to Krystahl, as both sage advice and warning, a reminder of her role as baylan. In a Philippines that has lost 97% of its primary forest, that remains one of the deadliest in the world for environmental defenders, and where discrimination abounds, a return of the baylan seems critical. Baradiya poses the question of a decolonial, future ecology that challenges boundaries between the physical and spiritual, between humans and nonhumans. In this, we look to the baylan to lead the way.

Written by John Altomonte.

Before you go, maybe share this newsletter with a friend, and then check us out on Instagram. Thank you for reading. We love you.

References

Brewer, Carolyn (1999). Baylan, Asog, Transvestism, and Sodomy: Gender, Sexuality and the Sacred in Early Colonial Philippines.

Jarman, Derek (1991). Modern Nature.

Kimmerer, Robin Wall (2015). Nature Needs a New Pronoun: To Stop the Age of Extinction, Let’s Start by Ditching “It”.

McCoy, Alfred (1982). Baylan : Animist Religion and Philippine Peasant Ideology.

The film Baradiya was made possible by its incredible cast and crew:

Directors: Gab Mejia, David Loughran, Antonio Lantong Dagoc Jr.

Cinematographer/DOP: Miko Reyes

Art Director and Ritualist: Alaga

Screenwriter: Nicola Sebastian

Sound Design: ((( O )))

Producer: Sam Turingan, JB Estrada

We use the term baylan for consistency here, however, regional variations are present throughout the Philippines, such as bailan, mabalian, or baylan among the interior populations of Mindanao and baylan or babaylan in the Visayan region of the central Philippines.

We use the terms man/woman (denoting sex and/or gender), male/female (denoting only biological sex), and masculine/feminine (denoting only gender). While indigenous Filipino peoples did not ascribe to such distinctions, we use them here to avoid confusion.

There are local and regional variations, but these distinctions are generally observed across southeast asian animist societies.